Architecture is not the “magnificent game of volumes under the sun” that Le Corbusier proclaimed, maybe dazzled by the scenery spotted from his packet boat on his Mediterranean journeys. When the external observer wonders at the contemplation of those volumes architecture, they are not living it but maybe just aspiring to possess it. The substantial idea is who those volumes shelter, their reason of being: the shadows that are generated in the inside.

Another more obscure Le Corbusier could proclaim that the architecture is the wise game of the artefacts of shadow against the sun. The shadow is the most probable and genuine product of any architectonic act. Once it is constituted, the shadow is what, through architecture, invites the light, treated as a guest in the habitable interiors.

Will that guest be a discreet soft invited today, who accompanies an intimate conversation? Will they behave as a cheerful visitor on a Saturday morning breakfast? Will they slide like a thief by the walls and will they stay steady, silent, glued to them? Will they go in on the sly, intense but thin between the chinks of Majorcan blinds, in order to caress lover bodies? Will they fall down like a cold shot on the page of a book? Will they loot a room like a battalion out of control, through a completely glazed wall? Will they arrive to the courtyards piercing the outline of vine leaves? ¹.

The shadow first appeared together with architecture, defining how the areas from which we invite the sun are, something which until then it disrespectfully bathed the steppes, beaches and wheat fields, but which now has to knock doors, hit roofs or spy through windows.

Louis Khan liked to quote the poet Wallace Stevens when he described the operation of open gaps on façades like the appropriation of “slices of the sun†(“What slice of sun does your building have?â€) ². A type of architecture which claims its existence from the inside to the outside and not the other way around. The builder of the habitable shadow limits fissures on its borders by means of which he takes over slices of light that come from a bright mass without shape there outside and that needs artisan hands, to be divided, sieved, made bounced ricochet till it softens, distilled or made to rain on the shape of golden threads.

The artist James Turrell has built his trajectory from the expression of “sewing lightâ€, proposing “spaces that catch light and keep it in order to be able to feel it physicallyâ€. In a reflection that goes back to “praise of the shadowâ€, he assures that “we are not made for so much light, we are made for twilight. What I want to say is that our pupil just dilates when very low intensities of light are reached. When it finally dilates we start to feel light, almost like if we touch itâ€.

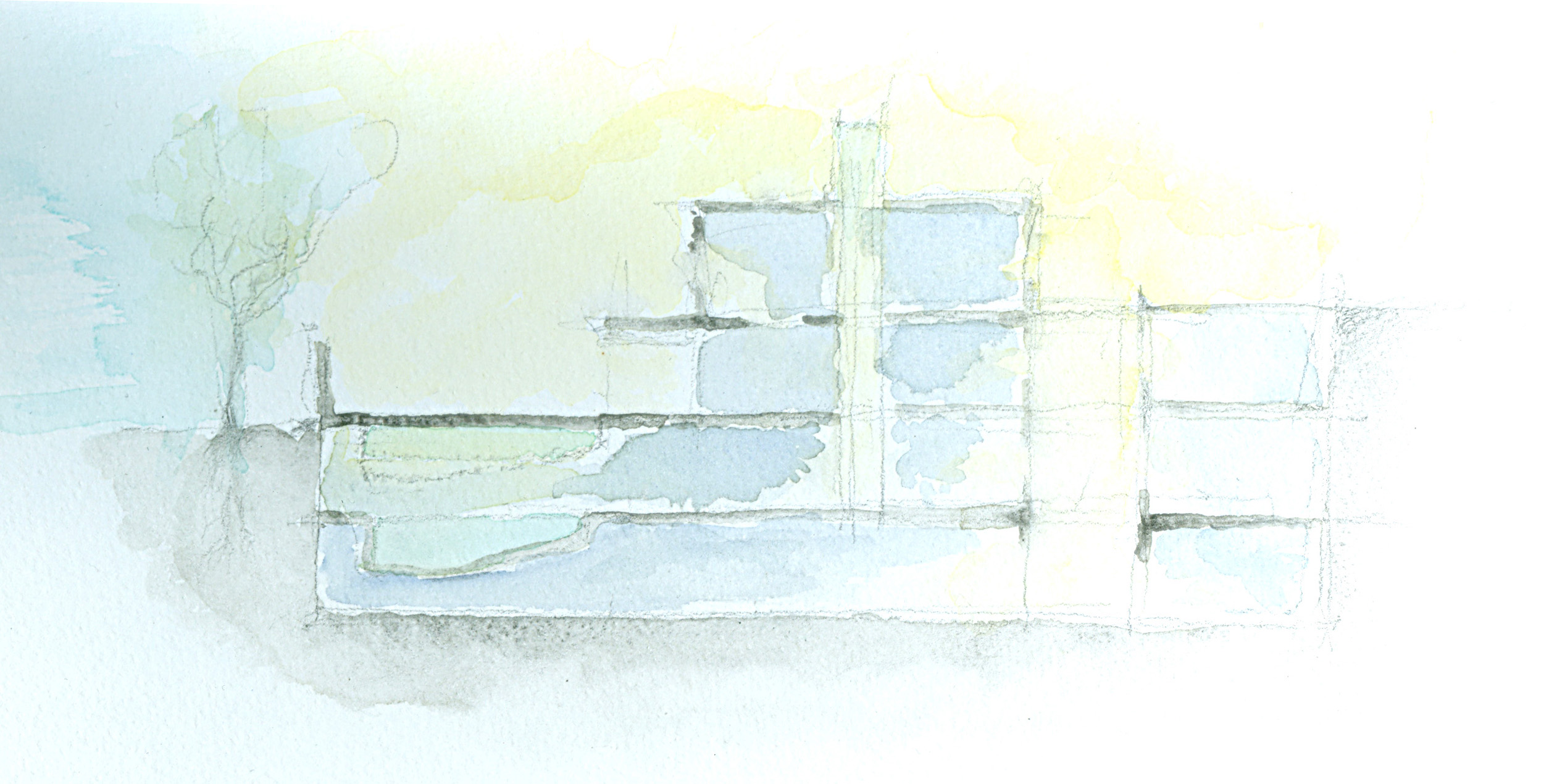

The single family home in the street Carmelo Torres in Jaen is shown to the street like an opaque prism of marble where two cuts stand out, two empty slices, one in the skylight and the other perpendicular one on the window of the first floor. It is a dwelling where the most habitable areas are placed under low-flying. There are two floors of basement that occupy all the surface of the plot (the most superficial with rooms and the deepest with a car park). There are two floors above low-flying that define an almost free-standing cube, separated from the street, in a way that some space is liberated at the southeast for the swimming pool and the garden.

That volume of shadow of four floors invites the light of Jaen from different types of cavities. The rear courtyard, polluted by near car parkings, spills a diffuse clarity above the car park situated at the level -2. At the crack that accompanies the lineal staircase, and which culminates with the prismatic skylight, the direct light of the south is invited to go over wood steps, from the flat roof to the garage. The English courtyard next to the exterior swimming pool is the entrance hall of indirect illumination of the spaces of the first basement, and, at the same time, it bathes the acclimatized interior swimming pool and the corner of the garage. The double height above the living room establishes a relation between the reflections of the garden water and the light that descends through the staircases.

At the centre of Jaen the sun light is a heavy and thick presence for many days every year. The constructions shape their volumes of shadow and then they negotiate how to invite the sun light, giving shape to the slices of light, to the filters and to the barriers. The built shapes do not play under that light, they just aspire to distil it within their stills and their gadgets. They are conceived to be domesticated.

¹ There is nobody better than the poet Wallace Stevens to describe the power of light beams over a courtyard: “Not all the knives of the lamp-post, / Nor the chisels of the long streets, / Not the mallets of the domes / and the high towers, / can carve / What one star can carve, / Shining through the grape-leavesâ€. The Auroras of Autumm, 1954.

² And he went on with metaphors of the same type: “The sun never knew how big it was until it hit the side of a building.â€