Anthony Vilder has tracked on his text “The warped space” about the pathological origin of a desire of modern urbanism for transparency and unspeakable space (using Le Corbusier terminology). It is easy to appreciate his desire on the romantic heritage of the concept of sublime, sometimes unspeakable and horrible, through illustrations of mystical and immeasurable landscapes, waiting for a storm or an appearance. At the same time, Vidler exposes on an analysis the real consequences of feelings such as claustrophobia or agoraphobia from authors at the beginning of the 20th century. He also says that this claustrophobia and the fear of touching could be the origin of the hatred towards a classical street from le Corbusier and Howard Roark, main character of “The Fountainhead”, a literary and film copy of most renowned architects at the time. Those endless prairies that surround those monumental glazed prism of Ville Radieuse or Voisin Plan from Le Corbusier or abstract mockups shown by Roark on the film are psychopathologically interpreted by Vidler:

“An endless space was used as an instrument of everything that Roark and Le Corbusier hated from a city, even a synonym of their own highly developed phobias repression. A traditional city represented claustrophobia and, related with it, a fear of touching, identified by Simmel.” When Le Corbusier proposed those enormous and majestic prisms for the endless prairie he refers to the principle of ruling throughout the history of modernism, either expressionist, functionalist, metaphysic or idealistic: transparency. Buildings adapted to space, absorbed and dissolved within it, penetrated by light and air, surrounded by vegetation.”1

Results from the trip Le Corbusier went on alongside Fernand Leger on 1935 show both extremes of empathy relationships towards a highly populated city. While Swiss architect ended up his American adventure with a theoretical proposal for the United Nations building (a splintered prism without roughness and isolated; a machine ready to work with extra streets), Leger took more advantage of it than his colleague: he attended several theaters, drove through motorways, visited bus garages after midnight and improved his English skills while drinking in bars. He felt at home.2

His later paintings show his immersion into the city and, with an appearance that resembled to collage, men, women and machines live closely together. These works tackle the immediacy derived from staring at something used, accepting the fragmented personality of daily life. Richard Sennet drew up the conceptual arch from Leger visions to the clarifying text of Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter “Collage city”, which shattered the conceptual basis from modernist urbanism.

Shared time and immediacy of objects and residents of a city (as well as Leger stay in New York) shape our perception of it and its processes.

Arahal Theater was launched in 2003 as a project and after a hazardous work process, which included several paralyzations due to economic problems from companies, was finished in 2013 without including its front main square urbanization (it was not until 2019 when it was finished. Meanwhile, we had the opportunity to take part in the construction of one of the other ambitious projects of that town, as it was its Sport Center and its indoor swimming pool.

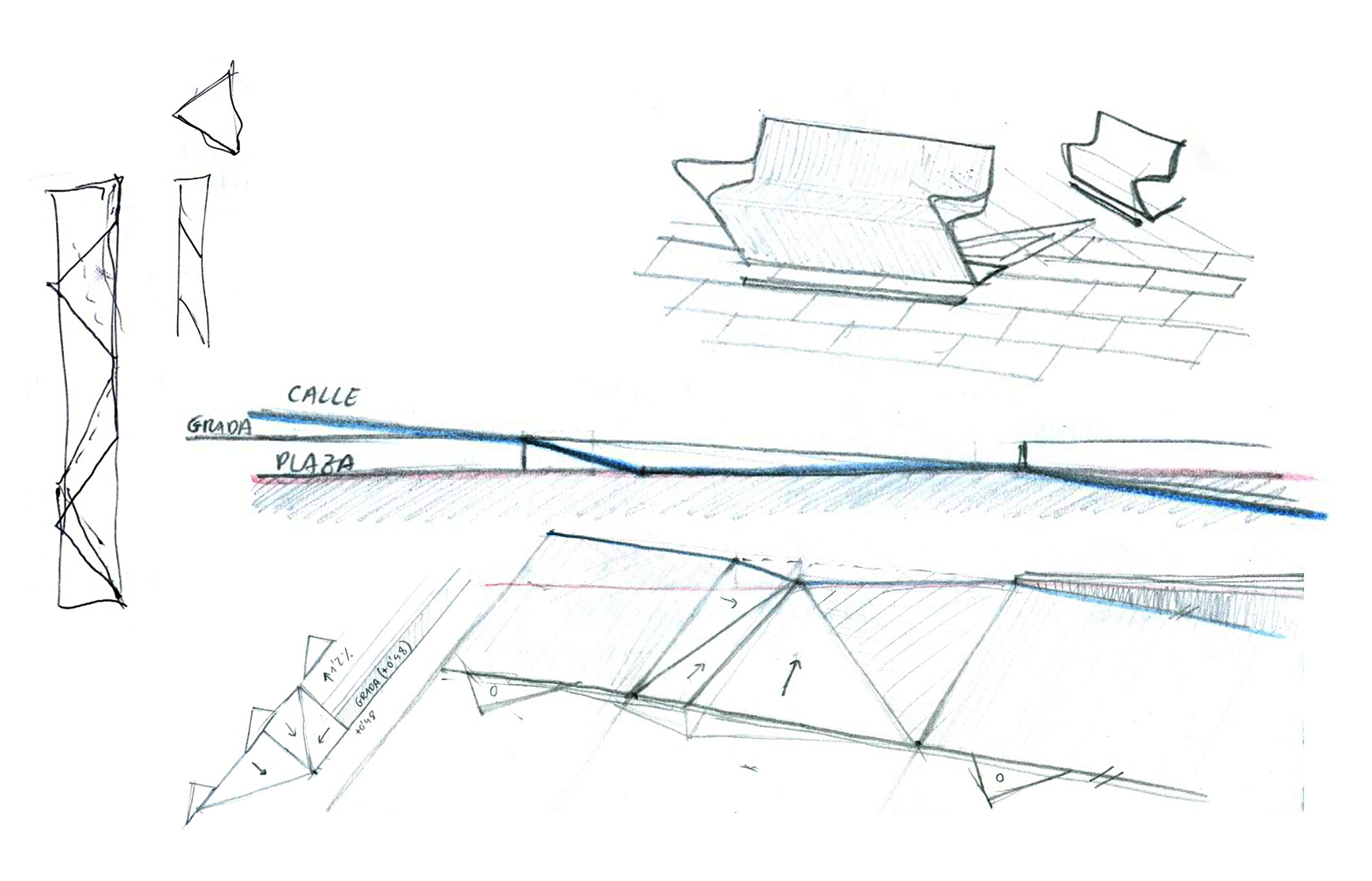

The so called Arahal Theater Square was launched as an abstract extended prairie with just one mediation of a splintered drawing, a diaphanous hall. Inner space reflected the exterior one as a mathematical mirror and the resulting triangular square from the enlargement of the building towards Avenida de la Estación was enough with a stone blueprint and a water plate, as well extended to the hall tickets box (another proposed reflection from interior-exterior).

When the time of building up the square came, people from Arahal felt “like at home” as Leger and this previous living room that always wanted to become a square was imagined as used and lively, asking for its furniture, its machines and people. Its shared collage. It also helped the theater consolidation throughout time as a model in the region, holding some ambitious programs of representations. Conversations with town hall managers while waiting to the square to be concluded dealt with the future role of this space, thought as an entrance hall to the scenic experience, fostering a transition where shadow, the rumor from tress tops or the surrounding sound of moving water favor leaving behind daily stress.

Thus, furnishing process from the initial abstract idea (with modernist roots) was beginning to come to life: a ficus promenade, fountains with several acoustic rumors, level changes and textures, street lights from the industrial past of the town, steel benches shaping the square, inviting to take a seat and helping to avoid sport activities, which may interrupt conversations and the intended vibes of the square. The monolith located on the edge of the acute angle has an historical association with the local theater and has a role on the connection between the abstract space and the city life.

This is the inevitable destiny of occupied abstractions. A canonical image of Ville Radieuse from Le Corbusier is a perspective in line where it is shown a project proposal of a green prairie with residential blocks on cross. This matches with the architect pathos but it does not go unnoticed to those who carefully observe the image that the author of the perspective (who imagines himself staring at his impressive urban view outlined against the horizon) had to furnished this specific space from which the visitor stare at. Thus, in front of a transparent utopia, that inhabited space by the author in the foreground is a pleasant mediterranean hall closed by a factory parapet, covered by a vegetation dome and furnished with Thonet chairs and tables, where there is a tablecloth and cafe set to enjoy a nice afternoon at the shadow.

A furnished unspeakable space.

1 Vidler, Anthony. Warped Space. Art, Architecture, and Anxiety in Modern Culture. The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2000.

2 Sennett, Richard. The Conscience of the Eye. The Design and Social Life of Cities. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1992.